A storywork research project exploring the distant past, past, present, and future visions of human-polar bear coexistence with Swampy Cree, Sayisi Dene, Métis, and Caribou Inuit Elders and Knowledge Keepers

Polar bears (wapusk; nanuq; sas; loor blaan; Ursus maritimus) and people have shared northern coastlines for time immemorial, yet concerns about polar bears coming into communities is increasing. As the Arctic warms and sea ice habitat declines due to climate warming, coexistence strategies between people and polar bears have become increasingly important. This study uses community-based participatory research; coproduction of knowledge; hands back, hands forward; and storytelling to document Indigenous knowledge of human–polar bear coexistence.

—

One goal of this research project is to provide to the community of Churchill with an approachable, engaging, and artistic way to interact with the research results through a podcast storytelling format—in the words of the participants themselves.

—

The podcasts below share stories, with permission, from the participants from a distant past, past, present, and future perspective.

Timeline

A timeline of significant Indigenous events and significant events related to polar bears in Churchill, Manitoba, Canada.

Cocreated and designed by research participant © Nickia McIver.

“I think this storytelling is what our people

used to use before, and I think there’s

a lot of healing in it.”

— Cree Elder

Initial podcast outputs are going through further audio leveling and polishing,

but are made available to the public below.

All knowledge shared on this website and in the podcasts below is copyrighted by the research project team © Katharina M. Miller / Royal Roads University. Following the Principles of OCAP® the knowledge holders own and control how this information can be used now and into the future. All content, including audio, transcripts, photos, and graphics cannot be used without permission, and if permission is granted all knowledge shared must remain fully intact in its original form to protect the knowledge from being taken out of context.

—

For more information or to request permission please email Katharina M. Miller at ktmillerphoto@gmail.com.

Podcasts

Episode One

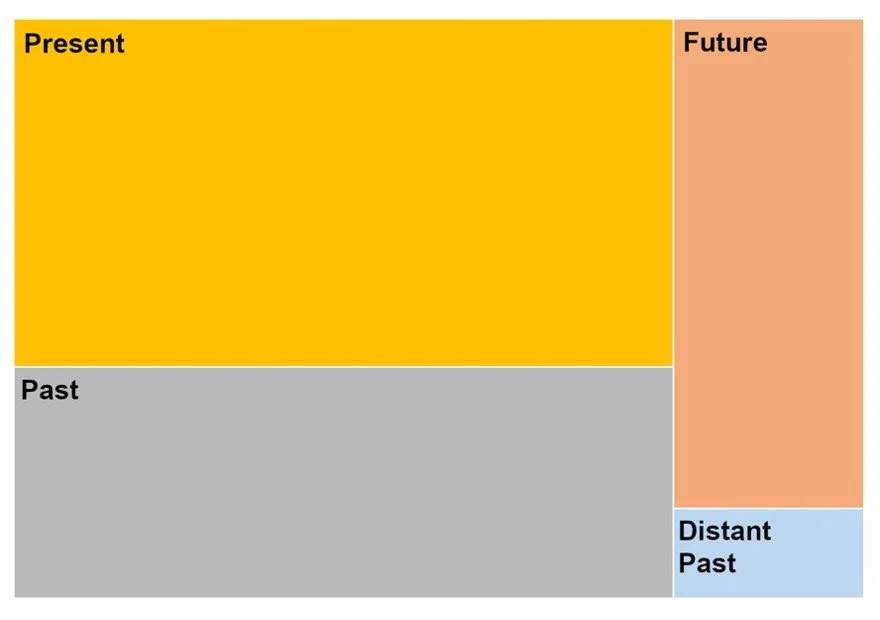

In the distant past, defined by this project as intergenerational knowledge prior to 1957, when the Cree and Dene were relocated to present-day Churchill, the fur trade was the primary economy on the shores of Hudson Bay. Polar bears were not often seen, and when spotted they were killed, with the meat primarily used for dog food and the hide sold to a trading post. Much intergenerational knowledge was lost when people were relocated to Churchill, where it was, to quote an Elder, “all about a new life.”

Episode Three

In the present, defined as 2005–2022 for this study, most people’s knowledge of polar bears came through tourism and Land-based activities. Of research participants, 83% were connected to tourism through their job in some way. Unlike their parents, children are now told not to play in the rocks or walk on the Pipeline. Many parents now drive their kids around town, especially at night, and raise their kids to always be bear aware, including having an exit plan when they are walking around town and utilizing buildings and vehicles to stay safe. Participants generally shared that living with polar bears is a normal part of life and emphasized that if the bears are respected, they will reciprocate that respect. The Cree, Dene, and Métis participants expressed they have the utmost respect for Inuit culture related to polar bears, and specifically Inuit rights to harvest polar bears for cultural, economic, and subsistence purposes.

Episode Two

From 1957–2005, defined by this project as the past, the era of the fur trade came to an end and a new era of tourism began. Participants recalled the military shot a lot of polar bears and kept the hides, hanging them on their walls or using them as rugs. They also recalled seeing large numbers of bears eating burning garbage at the open dump. Concurrently, tourism began and polar bears started to become more valuable alive than dead. In 2005, the open dump was closed and moved inside an old military warehouse (L5). Once the military left and the open dump closed, people started to see a lot more polar bears coming through town. Most participants’ first memory of a polar bear occurred during this time period, outside of a cabin at the Flats or a house in town, or at the dump. Even though all participants had encountered polar bears, many times, they did not speak of polar bears fearfully, but rather with respect and sometimes even humour and joy.

Episode Four

Participants had many visions for the future of human–polar bear coexistence in Churchill, which synthesized into the five main themes includes:

Protect tourism as an important industry and economy

Support proactive management and less invasive research

Elevate Indigenous knowledge in research and management

Improve bear safety education and awareness

Cultivate a culture of coexistence

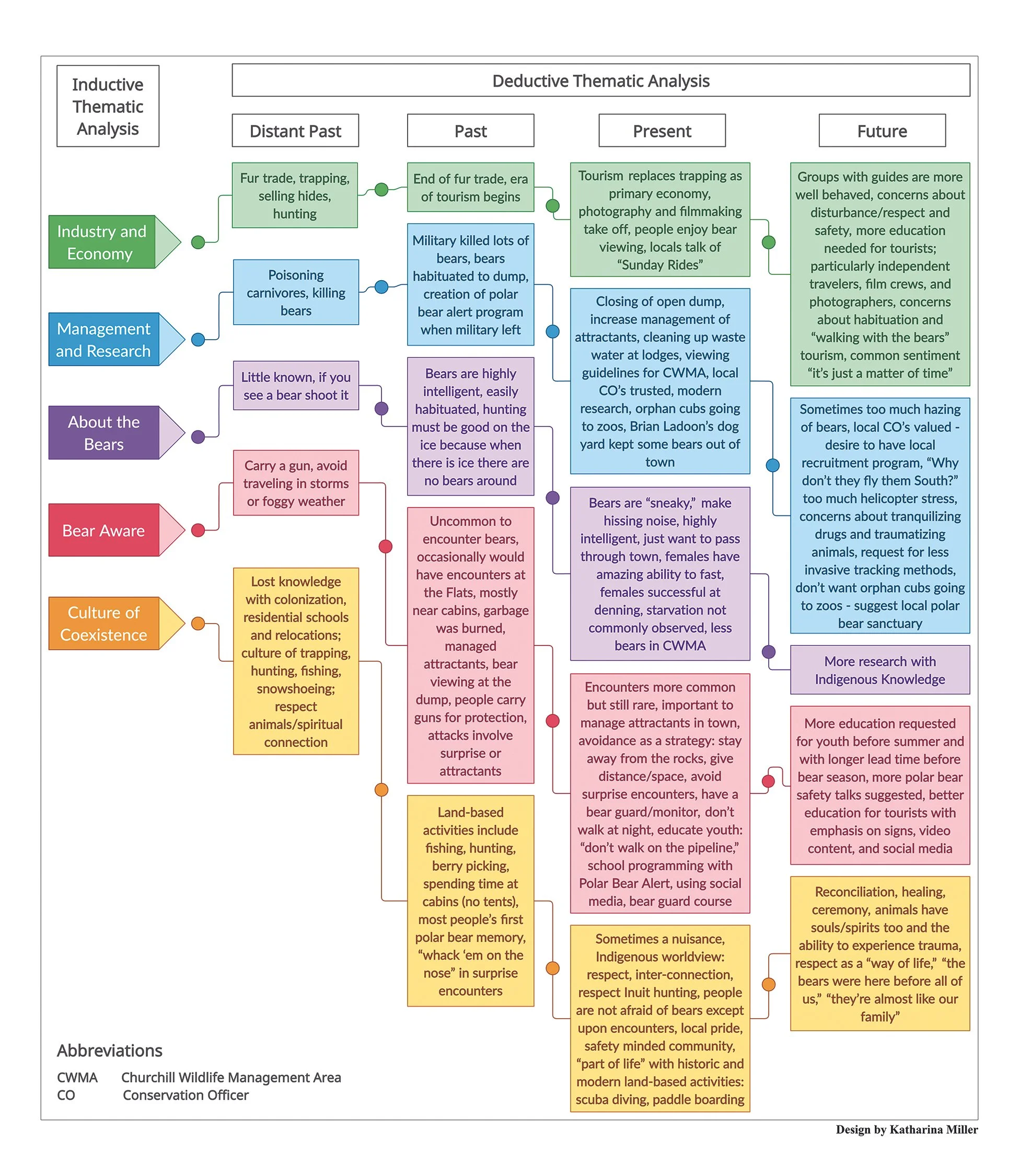

More detail regarding future visions articulated by research participants can be found in the figure below.

Future Visions & Recommendations

That bear’s going to pay the price for somebody’s stupidity of trying to get a picture, and I don’t think it’s fair.

— Research participant

How, the problem bears, when they take them out of jail and then they fly them north. I would like to know, like, is that really the best idea? Because I remember when Arviat didn’t really have a bear problem, and now they have a bear problem. Is it because we’re putting all of our bears there? Maybe there’s a better spot to take them, like maybe into the National Park, because that’s a big area where people don’t live.

— Métis participant

Tourists need to be educated more.

— Cree Elder

The coexistence thing is pretty critical, and it’s quite unique.

— Cree Elder

I’m trying to help other Indigenous peoples all across the country to recognize that tourism is big business, and it’s part of reconciliation, that can bring us back, and be used as an economic driver for our communities.

— Métis Elder

Knowing the way people personally react to stress: it can affect the way we sleep, the way we eat, the way, like our day-to-day life continues. I can only assume that it’s probably the same for different types of animals and species around the world.

— Research participant

They should have like some sort of apprenticeship program, for the next [Conservation Officers], it should be young local people following in their footsteps...

— Cree participant

Three maps of the Churchill region were coproduced to provide additional context for the knowledge shared.

Graphics cocreated and designed by © Nickia McIvor

Knowledge Holders

Research Design

This research was intentionally designed to braid Indigenous ways of knowing and western social sciences throughout the project, beginning with the ethical considerations all the way through theory, methods, analysis, and dissemination of results. Working with the Indigenous Knowledge Keepers, the mayor of Churchill, the participants, the community, and a Cree Elder as my coresearcher has been an honour and a true joy.

Storytelling

〰️

Community-based Participatory Research

〰️

Coproduction of Knowledge

〰️

Hands Back, Hands Forward

〰️

Synchonicity

〰️

Storytelling 〰️ Community-based Participatory Research 〰️ Coproduction of Knowledge 〰️ Hands Back, Hands Forward 〰️ Synchonicity 〰️

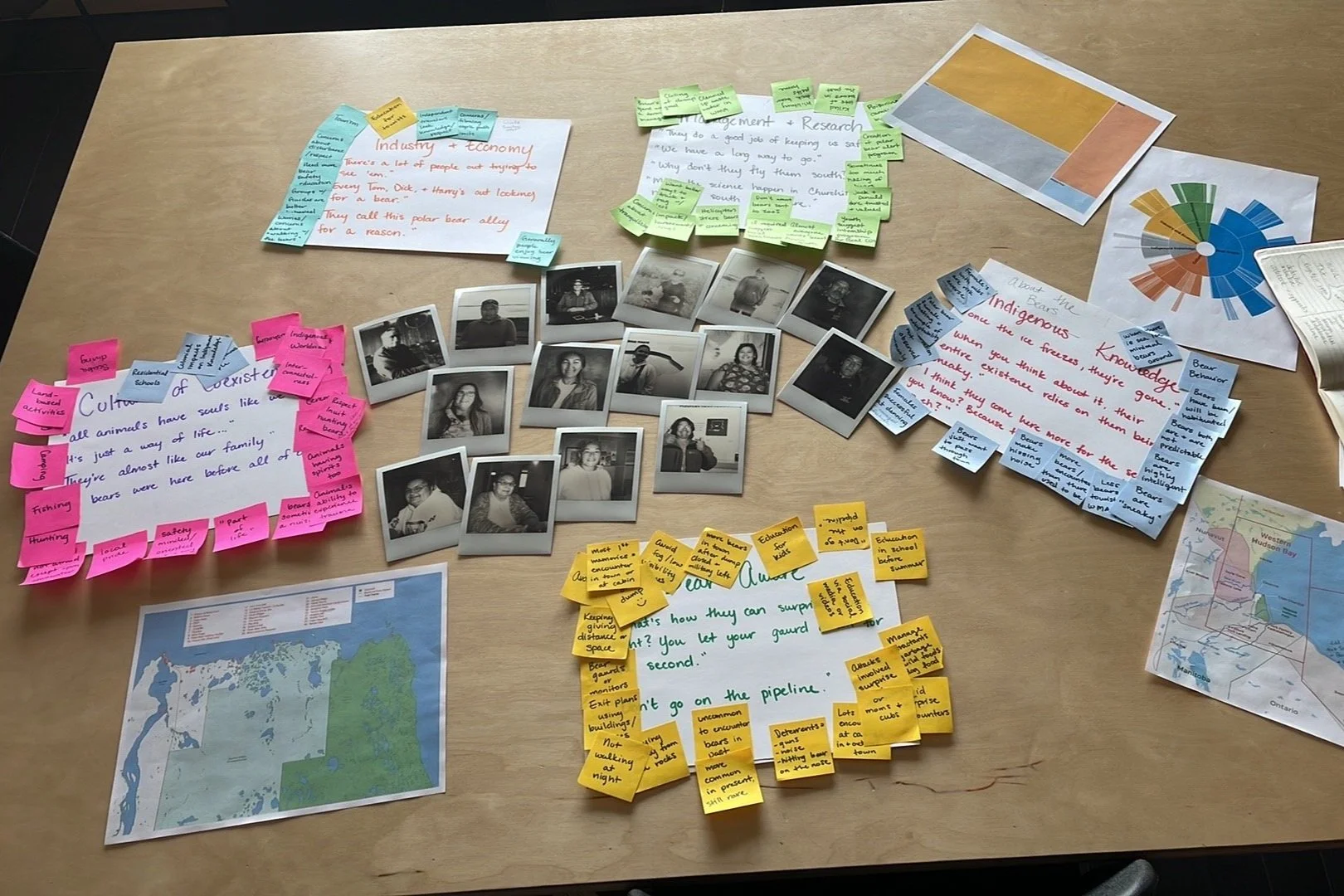

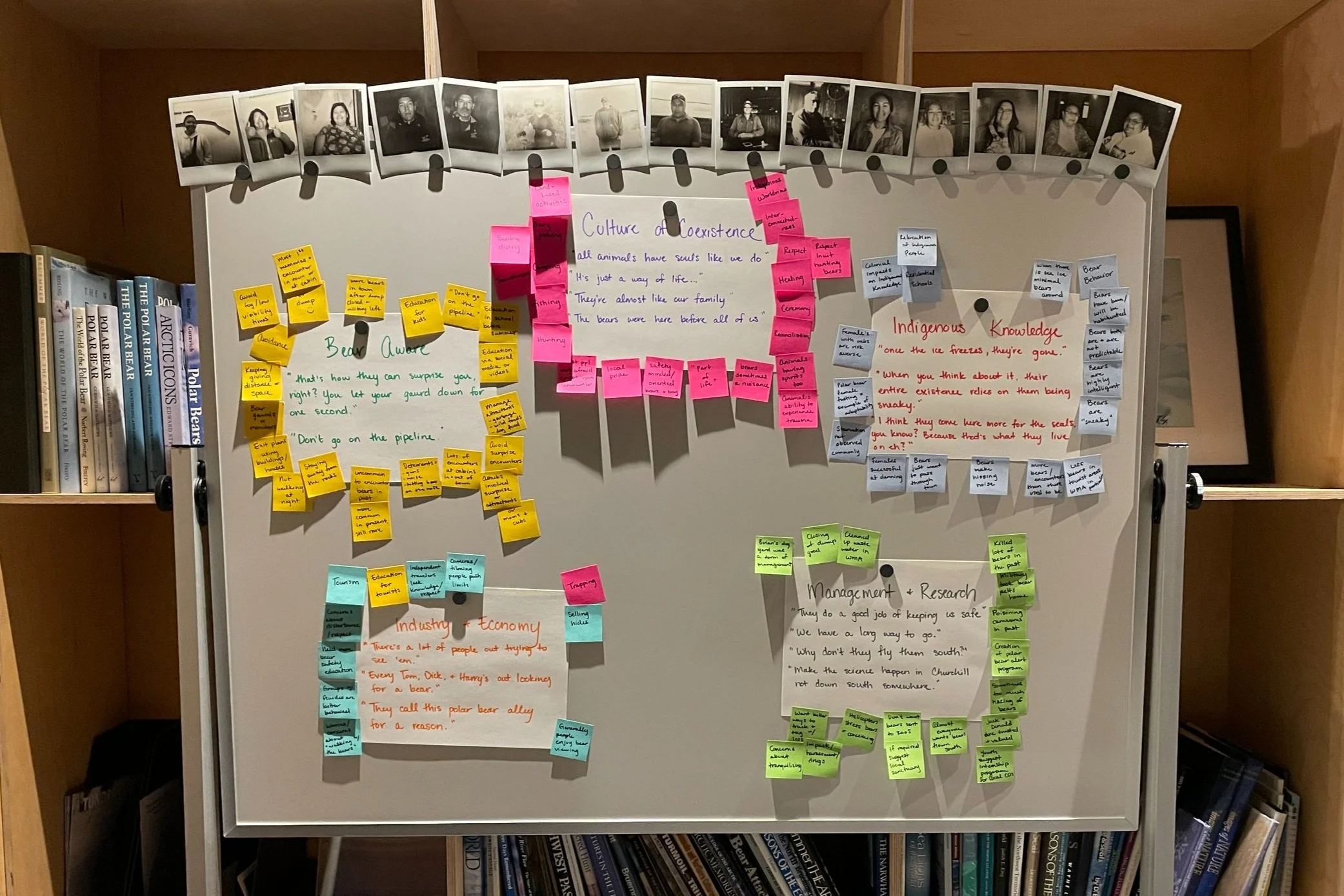

Analysis

On my second visit to the community for this research project, my coresearcher and I were discussing the process ahead. We had both been journaling over the summer, simultaneously, thousands of miles apart. Chapter 8 of the journaling book that we were following instructed us to go back to the beginning of our journals and circle the themes. When my coresearcher and I were together again in Churchill I exclaimed, “You’re already a researcher! That is what we are doing, that is how we will analyze our research, we will essentially go back through everything and look for, or circle, themes.” It was a moment of synchronicity and coproduction of knowledge that I will never forget.

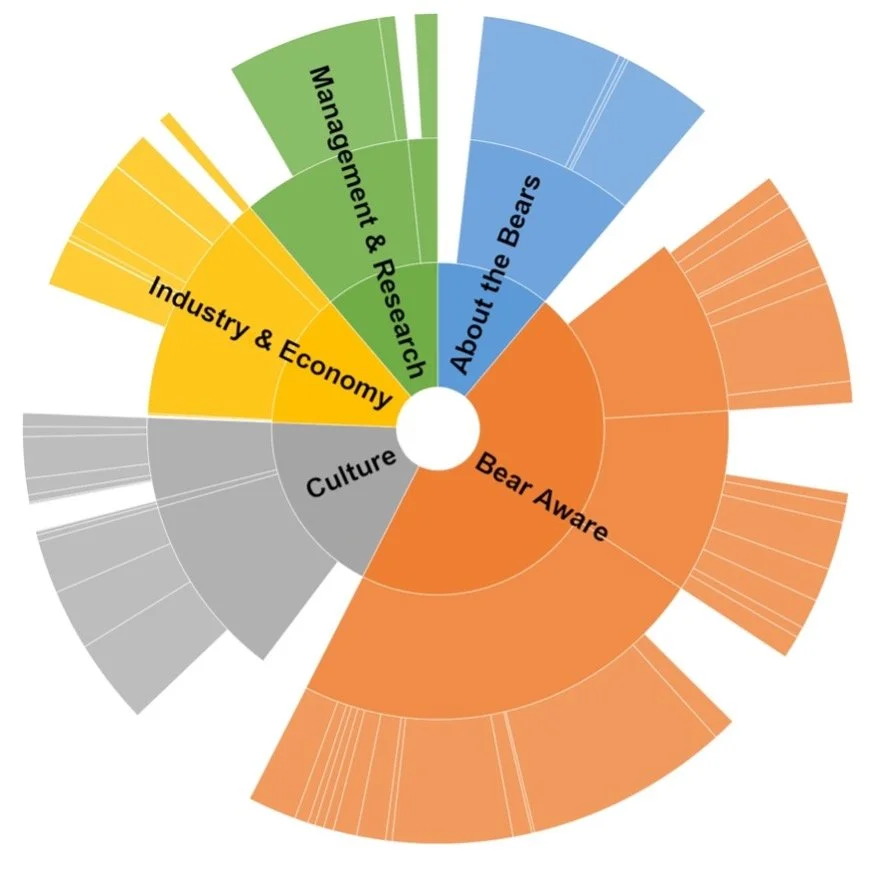

Sticky Notes (Turned into a Pretty Graphic) of the Inductive Themes

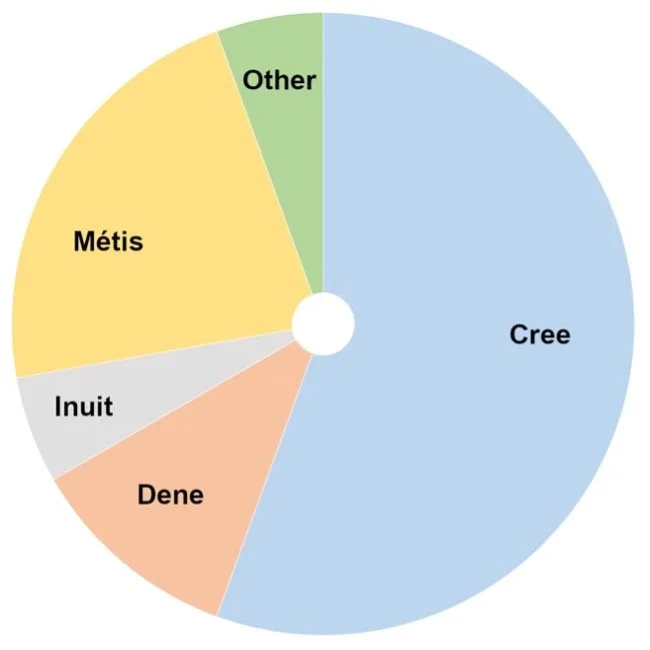

Breakdown of Participant Self-Idenfitication

Amount of Data by Time Period

Amount of Data by Theme and Subtheme

Throughout the analysis I went back and forth between audio editing software, social science coding software, and post it notes. The data was coded, or organized into inductive themes (patterns) and time based themes (distant past, past, present, and future). I returned to the community once to validate the inductive themes, and a second time to share and validate the podcast episodes. Each podcast is a storyline that weaves the inductive themes (patterns) with the time periods (deductive) that were significant in the context of the community and human-polar bear relations and interactions. Huge thanks to David Borish for sharing his video-based qualitative analysis method which inspired and informed this data analysis.

Community Presentation

Please enjoy this recording of the community feast and presentation in Churchill, Manitoba, Canada on October 7, 2023. Filmed and edited by Roy Mexted / Churchill Entertainment.

Self Location

Katharina (Kt) M. Miller

Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies, Royal Roads University

As a southern, white settler, it is important for me to ground and locate myself within this research. The topic of this Master’s thesis has been a curiosity of mine, grown into a hunch, that developed in nuance and complexity over a lifetime living and recreating with bears on the Lands of the Crow, Salish Kootenai, Cheyenne, Blackfoot, Sioux, and Shoshone Bannock, in the valley of the flowers, known as present day as Bozeman, Montana. Through extensive excursions travelling through the wilderness, particularly on skis, I developed an intimate relationship and sense of knowing through ecological, experience-based observations and time spent on the Land. This piqued my interest in experiential and place-based knowledge and ultimately led me to Indigenous ways of knowing. The intersection of this interest with over a decade of work with the nonprofit, Polar Bears International, spending 3 to 5 months each year in the community of Churchill, Manitoba, Canada, and developing deep friendships and personal investment in the community, has culminated in this interdisciplinary research inquiry.

This somewhat unconventional, interdisciplinary, mixed-methods, academic and creative endeavour has been a wild and fulfilling journey. My gratitude to those who made it possible is without limit.

Matna. Marrci. Masi Cho. Ekosi.

Thank you.

Contact Information:

Katharina (Kt) M. Miller

ktmillerphoto@gmail.com